Unveiling the Marvels of the Third Stage of Labor: Understanding Physiology and Anatomy

Abbie Tomson

Midwife MSc, BSc, Yoga Teacher, Project Lead at All4Birth

@enevlorel

As the culmination of the miraculous journey of birth, the third stage of labour marks the final chapter in the arrival of new life into the world. This stage, often overshadowed by the intensity of earlier phases, is nonetheless a critical and awe-inspiring period characterized by remarkable physiological and anatomical processes. This article delves into the intricacies of the third stage of labour, shedding light on the wonders that unfold during this transformative moment.

*At All4Birth we believe in a physiological approach and acknowledge that labour is defined into ‘stages’ which can be difficult to navigate given that labour is a continual process and physiologically wouldn’t be in distinct ‘stages’. It is known that the body was seen as a machine with birth becoming a process with stages, measurements and timelines in the 17th century. We are providing this information to help guide you through the terminology that your healthcare providers may use.*.

The Third Stage of Labour

The third stage of labour begins immediately after the birth of the baby and concludes with the delivery of the placenta. While it is typically shorter in duration compared to the preceding stages, its physiological significance is no less significant.

Physiology

– Uterine Contractions: Similar to earlier stages of labour, uterine contractions play a pivotal role in the third stage. These contractions help to compress blood vessels within the uterine wall, reducing bleeding and facilitating the expulsion of the placenta.

– Hormonal Regulation: Hormonal changes, including a surge in oxytocin levels, continue to drive uterine contractions and promote the delivery of the placenta. Oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” also aids in the bonding between mother and baby.

– Placental Separation: The detachment of the placenta from the uterine wall is facilitated by the separation of the maternal and fetal components of the placenta, a process initiated by uterine contractions.

Physiological Management

Physiological management of the third stage of labour refers to allowing the body to expel the placenta naturally, without the use of interventions such as artificial oxytocin (also known as syntocinon) or controlled cord traction. This approach aims to support the body’s natural processes and minimise the risk of complications associated with interventions.

Here’s how physiological management of the third stage of labour (can) work and how you can support physiology at this time:

1. Waiting for Signs of Placental Separation:

– Physiological management involves waiting for signs of placental separation, such as a change in the shape of the uterus, a lengthening of the umbilical cord, or a gush of blood.

2. Encouraging Skin-to-Skin Contact and Breastfeeding:

– Skin-to-skin contact between the mother and baby immediately after birth helps to stimulate the release of oxytocin, which promotes uterine contractions and facilitates placental delivery.

– Breastfeeding soon after birth also stimulates oxytocin release and helps the uterus to contract, aiding in the expulsion of the placenta.

3. Supporting Passive Management:

– Passive management involves allowing the placenta to birth spontaneously without active intervention.

– To support passive management, midwives may encourage the mother to rest and relax, avoiding unnecessary movement that could disrupt the natural process of placental expulsion.

4. Assisting with Maternal Positioning:

– Certain maternal positions, such as side-lying or upright positions, may facilitate placental delivery by allowing gravity to aid in the process.

– Healthcare providers may assist the mother in finding a comfortable position that promotes relaxation and optimal uterine contraction.

5. Monitoring for Signs of Complications:

– While waiting for the placenta to deliver, the midwife will monitor the mother closely for signs of complications, such as excessive bleeding (postpartum haemorrhage) or retained placenta.

– Prompt recognition and management of complications are essential to ensure the mother’s safety and wellbeing.

6. Encouraging Maternal Bonding and Emotional Support:

– Providing emotional support and reassurance to the mother during this time can help her feel empowered and confident in her body’s ability to birth the placenta.

– Encouraging bonding with the baby and involving the mother in the birthing process can distract from discomfort and promote a positive birth experience.

Duration:

On average, the placenta typically births within 30 minutes to an hour after the birth of the baby. However, it’s important to note that the duration can be longer in some cases, and it may take up to 1 to 2 hours or even longer for the placenta to birth physiologically.

Several factors can affect the length of time it takes for the placenta to deliver physiologically:

1. Previous Births: The length of time it takes for the placenta to deliver may be shorter in women who have previously given birth, as the uterine muscles may be more efficient at contracting.

2. Multiparity: Women who have had multiple pregnancies may experience shorter third stages of labour compared to first-time mothers.

3. Uterine Tone: The strength and tone of the uterus play a significant role in placental delivery. Women with a good uterine tone may experience shorter third stages of labour.

4. Maternal Positioning: Certain maternal positions, such as upright or side-lying positions, may facilitate placental delivery by utilizing gravity to aid in the expulsion of the placenta.

5. Breastfeeding: Skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding soon after birth can stimulate the release of oxytocin, which helps the uterus to contract and expel the placenta.

6. Complications: In some cases, complications such as retained placenta or abnormal placental attachment may prolong the third stage of labour, requiring medical intervention.

While physiological management of the placenta is generally considered safe for low-risk women, it’s essential for midwives to closely monitor the progress of placental delivery and intervene if necessary to prevent complications such as postpartum haemorrhage or retained placenta.

Active Management

Active management of the birth of the placenta is a proactive approach to facilitate the delivery of the placenta after birth. It involves the administration of uterotonic drugs and controlled cord traction to expedite placental expulsion and reduce the risk of postpartum haemorrhage (excessive bleeding after childbirth). This approach is typically recommended for women with specific risk factors or in settings where resources for close monitoring and intervention are readily available.

Components of Active Management:

1. Uterotonic Drugs:

– The most commonly used uterotonic drug for active management is synthetic oxytocin, also known as syntocinon or Pitocin.

– Oxytocin would be administered intravenously or intramuscularly immediately after the birth of the baby to stimulate uterine contractions and promote the expulsion of the placenta.

– The use of oxytocin helps to ensure a coordinated and effective contraction of the uterus, reducing the risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

2. Controlled Cord Traction:

– Controlled cord traction involves gentle pulling on the umbilical cord while simultaneously applying counter-pressure to the lower abdomen.

– This technique helps to facilitate the descent and expulsion of the placenta by guiding it through the birth canal.

– Controlled cord traction is typically performed after the administration of uterotonic drugs and when signs of placental separation are present.

3. Uterine Massage:

– Uterine massage involves applying firm, circular pressure to the lower abdomen to stimulate uterine contractions and aid in the expulsion of the placenta.

– This technique is often performed concurrently with controlled cord traction to enhance uterine contraction and ensure complete placental delivery.

Indications for Active Management:

Active management of the birth of the placenta may be recommended in the following situations:

1. High-Risk Factors:

– Women with risk factors for postpartum haemorrhages, such as prolonged labour, multiple gestations, macrosomia (large baby), or previous history of postpartum haemorrhage, may be recommended for active management to reduce the risk of complications.

2. Setting and Resources:

– In settings where resources for close monitoring and intervention are limited, active management may be preferred to minimise the risk of postpartum haemorrhage and ensure optimal outcomes for both mother and baby.

Statistics and Evidence:

Studies have shown that active management of the third stage of labour is associated with a reduced risk of postpartum haemorrhage compared to expectant or physiological management.

Duration:

The duration of active management of the birth of the placenta varies but typically takes around 5 to 30 minutes after the birth of the baby. Prompt administration of uterotonic drugs, controlled cord traction, and uterine massage can help expedite placental delivery and minimise the risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

Optimal Cord Clamping

Optimal cord clamping is a practice performed immediately after the birth of the baby, where the umbilical cord is clamped and cut after a brief delay, typically between 30 seconds to 3 minutes after birth. This delay allows for the transfer of blood from the placenta to the baby, maximizing the volume of blood and nutrients received by the newborn.

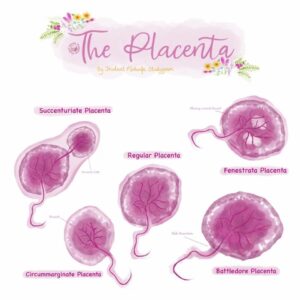

Anatomy and Physiology:

During pregnancy, the placenta serves as the lifeline between the mother and the baby, supplying oxygen and nutrients to the fetus through the umbilical cord. The umbilical cord contains two arteries and one vein encased in a gel-like substance called Wharton’s jelly. The umbilical vein carries oxygen-rich blood and nutrients from the placenta to the baby, while the umbilical arteries carry deoxygenated blood and waste products from the baby to the placenta for elimination.

At birth, the baby takes its first breath, initiating changes in the circulatory system. As the baby’s lungs expand and begin to function, pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, and blood flow to the lungs increases. This shift in circulation leads to an increase in blood volume returning to the left side of the heart, which in turn increases systemic arterial pressure.

Benefits of Optimal Cord Clamping:

1. Increased Blood Volume: Delayed cord clamping allows for a greater volume of blood to be transferred from the placenta to the baby, resulting in increased red blood cell mass and haemoglobin levels. This additional blood volume provides the baby with a reserve of oxygen and nutrients, reducing the risk of anaemia and promoting healthy development.

2. Improved Cardiovascular Stability: The additional blood volume obtained through delayed cord clamping helps to stabilize the baby’s cardiovascular system, maintaining blood pressure and circulation during the transition to extrauterine life. This can be particularly beneficial for preterm infants or those born with low birth weight.

3. Enhanced Iron Stores: Delayed cord clamping has been shown to increase the baby’s iron stores, which are essential for healthy growth and development, particularly in the first few months of life. Adequate iron stores help prevent iron deficiency anaemia and support neurodevelopmental outcomes.

4. Reduced Risk of Intraventricular Hemorrhage: Studies have suggested that delayed cord clamping may be associated with a lower risk of intraventricular haemorrhage (bleeding in the brain) in preterm infants, possibly due to improved cardiovascular stability and cerebral perfusion.

5. Improved Transition to Extrauterine Life: Delayed cord clamping allows for a smoother transition to breathing on their own, as the baby receives a steady supply of oxygenated blood during the critical moments after birth. This can help reduce the risk of respiratory distress and other complications associated with neonatal transition.

Conclusion

The third stage of labour represents the culmination of the miraculous journey of childbirth, marked by the delivery of the placenta. Through a symphony of uterine contractions, hormonal regulation, and anatomical adaptations, the maternal body orchestrates the final act of bringing new life into the world. Understanding the physiology and anatomy behind the third stage of labour deepens our appreciation for the complexity of childbirth. It highlights the resilience and adaptability of the human body in this transformative process.

Links to resources

Books

Books

Film Audio and Apps

Film Audio and Apps

Baby Buddy app, created by the Best Beginnings Charity

The Midwives Cauldron- Placentas and Cord Blood Podcast

Birthful Podcast- Third Stage of Labour

Websites

Websites

Midwife Thinking: An actively managed placenta may be the best option for most women‘

Sara Wickham- Can I have a natural placental birth after induction?

Sarah Buckley- Leaving Well Alone: A Natural Approach to the Third Stage of Labour

References

- Begley, C. M., Gyte, G. M., Devane, D., McGuire, W., Weeks, A., & Biesty, L. M. (2019). Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2(2), CD007412. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub5

- Begley, C. M., Gyte, G. M., Devane, D., McGuire, W., & Weeks, A. (2015). Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3), CD007412. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub4

- World Health Organisation (2014) ‘Active Management Of The Third Stage Of Labour: New WHO Recommendations Help to Focus Implementation’. Available at:

- Reed, R., Gabriel, L., & Kearney, L. (2019). Birthing the placenta: women’s decisions and experiences. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 19(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2288-5

- Saxton, A., Fahy, K., Rolfe, M., Skinner, V., & Hastie, C. (2015). Does skin-to-skin contact and breast feeding at birth affect the rate of primary postpartum haemorrhage: Results of a cohort study. Midwifery, 31(11), 1110–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.07.008

- Charles, D., Anger, H., Dabash, R., Darwish, E., Ramadan, M. C., Mansy, A., Salem, Y., Dzuba, I. G., Byrne, M. E., Breebaart, M., & Winikoff, B. (2019). Intramuscular injection, intravenous infusion, and intravenous bolus of oxytocin in the third stage of labor for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage: a three-arm randomized control trial. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 19(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2181-2

- Yildirim, D., Ozyurek, S. E., Ekiz, A., Eren, E. C., Hendem, D. U., Bafali, O., & Seckin, K. D. (2016). Comparison of active vs. expectant management of the third stage of labor in women with low risk of postpartum hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Ginekologia polska, 87(5), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.5603/GP.2016.0015

- Coad, J. (2019). Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives. Elsevier.

- Marshall, J. E., & Raynor, M. D. (2019). Myles Textbook for Midwives. Elsevier.